This piece has been put together by Dr Raj Shah, Haile Mistry, Mathew Roshan and Gavin Thomas

This paper examines the benefits of the research conducted regarding the source and its compatibility with current diesel engines, as a solution in the meantime.

Solvent extraction and pyrolysis have helped reveal the benefits the liquid provides, looking from the molecular level to the comparable efficiency like diesel, while in hopes of reducing emissions.

Valorising CNSL provides an opportunity to support circular economic principles, converting agricultural waste into energy.

Although challenges remain regarding large-scale production, CNSL-derived fuels offer a sustainable, low-cost alternative, contributing to a cleaner maritime industry.

Introduction

Af ter reportedly hitting historic lows , the global maritime trade is reaching a period of fragile growth [1].

In recent forecasts, the anticipated rise is also expected to be the slowest pace in years, reaching only 0.5% in 2025, as stated in the Review of Maritime Transport 2025, published by the United Nations (UN) [1].

As climate pressures and regulations tighten, the vulnerabilities in the global economy and shipping are exposed.

The industry faces rising costs and operational challenges to comply with measures such as MARPOL Annex VI, pushing for limiting sulphur oxide (SO2) emissions [2].

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI), and Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) regulations [3].

Additionally, facing pressures globally at the different ports, to name one, the European Union’s Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (EU MRV) framework mandates greenhouse gas reporting for ships sailing to EU ports.

With these mandates leading to increased costs and routes continuing to rise, the industry must quickly find solutions to its global impact.

Recent insights suggest that the shipping industry supplies over 80% of the world’s merchandise for export and import [1, 4].

With recent hopes to alleviate increasing global greenhouse emissions, the maritime industry realizes the trend is not going in the direction they were hoping for, facing pressures from organisations to modernise or find a lasting solution to reduce their environmental impact.

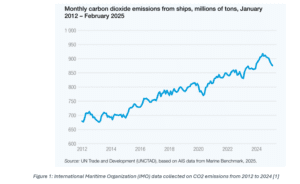

In order to limit greenhouse gas emissions in the maritime shipping industry, there has been an increase in research into compliant alternative fuels in the primary scientific literature. According to the International Maritime Organization (IMO), emissions rose from 4.7% between 2020 and 2021, increasing in the following years. This trend was reflected in the CO2 data reported by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), as seen in Figure 1 [4].

In addition, the average fleet age poses an issue, as many of the older models of these ships are prone to causing more pollution, emphasising the need for investment to reduce the carbon footprint produced by the maritime industry.

However, a solution that remains compatible with current fleet engines as a supplementary resolution could potentially mitigate some environmental concerns in the meantime.

The push to decarbonise has become a global race, intensifying the search for a scalable biofuel solution.

Meanwhile, long-term solutions remain heavily researched. Supplementary biofuels are being researched extensively by researchers to explore alternative fuels compatible with engines and fleets to reduce emissions.

In the waste streams of the nut, the waste is proving to be quite beneficial, too. Cashew nut shells (CNS) have been processed for quite some time to be converted into eco-friendly packaging and other uses.

In many countries and regions where these nuts are grown, such as South America, Central America, Africa, and Asia, these nuts are heavily produced but remain largely underutilised [5].

The shell represents 70-75% of the weight of the nut, but despite the large production and advantages, the waste isn’t widely used [6].

In India, there is often a lack of skilled manpower capable of roasting the nutshells. Due to this, the methods previously used to disregard the shells' release thick black smoke due to natural oils, which creates a public nuisance and even further pollution [6].

If not done using that method, the shells are dumped into the wild, but can then become toxic, polluting the soil [7].

Rather than contributing to more pollution, this waste stream presents an opportunity to practice the concept of valorisation, changing a once-hazardous waste into a potential practical biofuel source.

While the cashew kernel is the most valuable part, the shell has also proven to have a fair amount of value.

Cashew nutshell liquid (CNSL) is a reddish-brown viscous liquid found in the honeycomb structure of the shell [7].

Two types of CNSL have been derived through extraction, resulting in either natural or technical CNSL, each containing a different abundance of phenolic structures [8].

Natural CNSL is extracted using solvent-based methods such as hexane; the resulting phenolic structures include anarcadic acid and cardol [8].

In contrast, technical CNSL results in a high percentage of the cardanol and cardol phenolic structures.

These phenolic structures are like those found in traditional petroleum-derived fuels. While CNSL in its raw form remains unsuitable for direct use due to polymeric content, derivative blends or changes in the formulation pose as promising alternative biofuel candidates [9, 10].

In addition, CNSL fuel derivative blends exhibit characteristics like diesel.

The blends present a viable, low-cost alternative with potential to be enhanced and further improved with additional research.

In terms of changing the waste product into a fuel source, it has its own benefits too.

For example, a study by Sanjeeva et al. showed that blending tallow oil or straight vegetable oil (SVO) with CNSL as an additive could remain stable over 18 months without the need for transesterification, indicating CNSL’s potential for direct use.

Eliminating the traditional first step of transesterification provides not only economic advantages but also environmental advantages [9].

The liquid has many unique properties, not only high phenolic content but unique molecular structure, which combines aromatic phenolic rings and hydrophobic chains [10].

Differentiating CNSL from traditional biofuels, as many often lack molecular structures like petroleum-derived fuels.

The multiple reactive sites present in the chain enable blending strategies without extensive processing, as well.

Phenolic compounds often have their own benefits, providing a compound with thermal stability and antioxidant behavior, enhancing fuel storage and stability, and reducing the ability to degrade over time [11].

This is especially relevant to maritime applications, where these fuel sources are often stored in the long-term.

As a result, CNSL derivatives could provide a pathway for drop-in marine biofuels that meet the durability and stability needed from the fuels, while still providing an eco-friendlier solution [12,13].

Valorisation and physicochemical properties

In previous research conducted, the composition of these heat-treated cashew nut shells primarily consists of high-carbon biochar, often using sugarcane molasses as a binder and residual energy-rich bio-oil, ultimately producing a solid biofuel.

After solvent extraction (acetone, hexane, water), the extractives were isolated, followed by HPLC/UV analysis to determine the chemical composition and fuel properties [14].

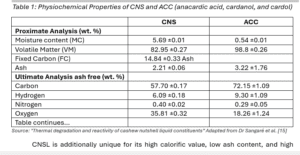

The biochar itself contains 57.70% carbon, 6.09% hydrogen, 35.81% oxygen, with a low ash content of 2.21% and low sulphur, which is key when addressing the issues IMO mentioned regarding the current fuel sources being used [14].

In this study, adding sugarcane molasses improves the mechanical strength, cohesion, and water resistance without significantly affecting the energy content, aiding the consistency in size and density of the briquettes.

But the high energy content of 35.8 MJ/kg exemplifies just one outcome of how the CNSL can be a valuable product [7, 14].

CNSL is additionally unique for its high calorific value, low ash content, and high volatile matter, to name a few properties [7].

One downside of CNSL is its high acid levels, leading to high corrosivity, affecting engine performance and causing decay over time .

Researchers have attempted to combat these issues by creating fuel blends to remediate the risks associated with the high acidity.

One example was creating a blend of 20% CNSL biofuel, exhibiting similar characteristics to those of diesel, which helped with its compatibility with diesel engines too [9] .

In this study, conducted by Dr Sanjeeva et al. investigated improving the properties of CNSL biofuel. Investigating how to mitigate the risks that polymeric content and acidity found in CNSL cause by creating the blends.

While these blends show promise, further research is needed to fully assess engine compatibility to prevent potential problems such as clogging or reduced efficiency. Looking into the potential methods to mitigate the issues caused by raw CNSL provides a potential pathway to a green solution, since most of the engines used in Maritime fleets are diesel.

Pyrolysis

Though interest in CNSL liquid continues expanding past niche applications, attention has shifted to unlocking the full potential and composition, through thermochemical pathways using pyrolysis.

Pyrolysis is a concept that involves the thermochemical decomposition of biomass in the absence of oxygen, resulting in three primary products: bio-oil, syngas, and biochar [7,15].

The technique has proven advantageous for converting agricultural residue into energy-dense fuels, supporting the concept of valorsation.

Unlike traditional combustion practices, it has the potential to preserve energy within the feedstock, making it beneficial for fuel-based applications. This is especially beneficial for CNSL due to the oil-producing carcinogenic smoke.

For cashew nut shells, the concept is well-suited. Recent research has shown the influence of extractives on the thermal stability of biomass.

Compared to wood containing 2-5 wt. % or in tropical species up to 15 wt.%, they are significantly lower than the 58 wt. % of extractives found within cashew nut shells [7].

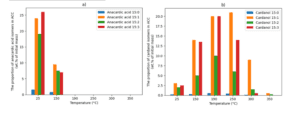

The most abundant extractives are ACC (anacardic acid, cardanol, and cardol) [7, 15]. Recent analysis methods conducted by Dr Sangaré et al. also allow for further individual ACC isomer analysis and their influence with pyrolysis temperatures, providing insight into both chemical composition and thermal transformation pathways (Fig. 2) [15].

These compounds contain aromatic structures and long hydrocarbon chains, characteristics aligning with those of petroleum-derived fuels compared to typical biomass-derived bio-oils. As a result, pyrolysis of cashew nut shells has the capability of yielding chemical products richer and energy-dense compared to standard wood-based pyrolysis oils [7].

In recent efforts, the transition from simple material characterisation to more complex material characterization has taken precedence.

Allowing for a deeper view of the complex composition seen in CNSL. Two types of pyrolysis have helped further this understanding, thermogravimetric and fixed-bed pyrolysis [7]. Together, they have helped researchers understand important characteristics of CNSL regarding degradation temperatures, kinetics, and product distributions, to understand the scalability of this biofuel.

Although previously used thermochemical pathways, such as gasification or hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL), pyrolysis offers advantages, the scalability was limited as they often added complexity and costs [7].

The other pyrolysis methods mentioned can provide a balanced mixture of liquid and gas, not just focusing on syngas or wet biomass.

Additionally, it creates the possibility of producing solid products suitable for direct fuel application. An advantage for maritime deployment, as it not only provides one pathway but also the possibilities of producing a bio-oil that can be directly upgraded or blended.

Like many processes, effective pyrolysis begins with proper feedstock conditioning to ensure results can properly reflect the behaviors. In one study, conducted by Dr. Sangaré et al., the cashew nut shells (CNS) were frozen at -80°C and then ground into 1-2mm particles to prevent any leaking of the extractives [7].

Extractives were removed by a triple solvent following the Soxhlet extraction process to generate the CNS fractions. As a result, the acetone extractives were rich in anacardic acids, cardols, and cardanols, accounting for roughly ~42 wt. % of CNS [7].

In contrast, hexane and water extractives were ~2 wt. % and ~18 wt. %, respectively [7]. In addition, analyses revealed the lower heating value of CNS close to 23.6 MJ/kg, volatile matter of 82.95 wt. %, and carbon content of 56.07%, showcasing the suitability of CNS as a high-energy feedstock [7].

Pyrolysis experiments were conducted using the two methods mentioned: a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) to understand the kinetics and a fixed-bed reactor to quantify the permanent gas and condensates produced [7].

For TGA samples, less than 10 mg were heated based on ambient (25 °C to 125 °C) or isothermal drying. For fixed-bed experiments, CNS particles (<1mm) were filled into a quartz tube and placed inside the reactor [7]. The tube was then heated to 400 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min. After the nitrogen addition, the gas was continuously analysed by MicroGC VARIAN CP 4900, and condensates were collected at the end [7].

Based on the results seen in the composition, CNS pyrolysis bio-oil is chemically distinctive due to its high phenolic content and aromatic structure.

These results were similar across other studies, too [15]. The ACC isomers were dominant in the acetone extractives.

This is important as it improves the thermal stability and antioxidant capacity, beneficial for maritime fuel applications. In addition, its lower heating value exceeds that of typical wood-based pyrolysis oils due to the high calorific value of CNSL [7, 15]. In other research, the low sulfur content provides a clear advantage over the IMO regulations and the goal of 2050, aiming to limit the carbon and sulfur footprint [4].

Although CNSL does prove to have challenges in its raw form, combined with the research regarding fuel blends and advances to limit its effects on the engines, it provides a potential solution for the Maritime Industry.

Future outlook and conclusion

Despite its clear potential, several challenges are still present, limiting the use of CNSL-derived biofuels. Issues regarding residual acidity, corrosivity, and long-term stability would need further development [15].

Variability in feedstock composition complicates process consistency due to different regional practices and processing methods. In addition, scaling the methods used to create many of the CNSL extractions remains a technical and economic disadvantage.

Although the research is still extensive and requires continued research and collaboration, there are many possibilities in the future to create a scalable alternative maritime fuel with CNSL.

For the maritime industry specifically, solid biofuel offers advantages to reducing greenhouse gas emissions with a high-energy alternative to marine diesel, compatible with the engines. Opting for a solid biofuel can help provide easier transport and storage, vital when being used on ships.

Moreover, the valorisation of this agricultural residue can help support the increased efforts of circular economy principles and shipping companies better adhere to the increasingly stricter regulations on fuel sustainability [14].

The circular economy concept is helpful here, as we can now utilize the entire fruit, reducing the pollution created from traditional processing, and a biofuel for the maritime industry to alleviate environmental concerns [16,17].

Maritime fuel even contributes to the increasing climate change problems. Although there is work to still be researched and methods to be refined for scalability, it provides a hopeful aspect of ways it could benefit the industry.

Not only does it provide environmental and economic benefits, but the idea of using it as a drop-in fuel has its own benefits.

The concept of drop-in fuels can be used without major modifications to an existing engine or fuel system, creating a good opportunity to reduce the carbon footprint and emissions. Unlike other biofuels generated from edible products, the benefit of being inedible also helps in reducing the amount of waste produced and does not affect the abundance or availability of the material long term.

Overall, while there are still refinements, CNSL proves to be a potential waste-derived biofuel. Its unique structures and similarities to those of traditional fuels make it a promising option for the maritime industry as the shift to a net-zero emissions future is prioritized [1,4].

More broadly, CNSL highlights the lesser-known value of agricultural residues, encouraging a shift in perspective. Bringing light to concepts, including but not limited to valorisation, circular economy, and so much more. It bridges current fuel with cleaner alternatives. CNSL provides a steppingstone toward a lower-carbon, environmentally friendly shipping industry.

Dr. Raj Shah is a director at Koehler Instrument Company in New York, where he has worked for the last 25 plus years. He is an elected Fellow by his peers at ASTM, IChemE, ASTM, AOCS, CMI, STLE, AIC, NLGI, INSTMC, Institute of Physics, The Energy Institute and The Royal Society of Chemistry. As an Adjunct Professor at the State University of New York, Stony Brook, in the Department of Material Science and Chemical Engineering, Raj also has over 750 publications and has been active in the energy industry for over 3 decades. https://tinyurl.com/mbz22vjv

Haile Mistry is an undergraduate Chemical Engineering student at Virginia Tech with experience in pharmaceutical process engineering, materials research, and engineering outreach. She is currently an undergraduate researcher in the Bortner Lab for Polymer Composite and Materials Laboratory, where her work focuses on biopolymer-based nanocomposites and additive manufacturing under Dr. Michael J. Bortner.

Mathew Roshan is an undergraduate in Chemical and Molecular Engineering at Stony Brook University. He conducts research at the Institute of Gas Innovation and Technology, focusing on sustainable energy systems under Professor Devinder Mahajan.

Gavin Thomas is part of a thriving internship program at Koehler Instrument Company in Holtsville, NY and is a recent graduate of the Chemical and Molecular Engineering program at Stony Brook University.

Works Cited

[1] U. N. C. on T. and D., Review of Maritime Transport 2025: Staying the course in turbulent waters. 2025. Accessed: Dec. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/rmt2025_en.pdf

[2] “Annex VI - Regulations for the Prevention of Air Pollution from Ships.” Accessed: Jan. 04, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.imorules.com/MARPOL_ANNVI.html

[3] “EEXI and CII - ship carbon intensity and rating system.” Accessed: Jan. 04, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.imo.org/en/mediacentre/hottopics/pages/eexi-cii-faq.aspx

[4] “Review of Maritime Transport 2022 | UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD).” Accessed: Dec. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://unctad.org/rmt2022

[5] N. Aslam et al., “Exploring the potential of cashew waste for food and health applications- A review,” Future Foods, vol. 9, p. 100319, June 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.fufo.2024.100319.

[6] A. Mohod, J. Sudhir, and P. A.G, “Pollution Sources and Standards of Cashew Nut Processing,” American Journal of Environmental Sciences, vol. 6, Apr. 2010, doi: 10.3844/ajessp.2010.324.328.

[7] K. W. Y. Chung, J. Blin, C. Lanvin, E. Martin, J. Valette, and L. Van De Steene, “Pyrolysis of cashew nut shells-focus on extractives,” Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, vol. 179, p. 106452, May 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.jaap.2024.106452.

[8] E. Bloise, M. Lazzoi, L. Mergola, R. Sole, and G. Mele, “Advances in Nanomaterials Based on Cashew Nut Shell Liquid,” Nanomaterials, vol. 13, p. 2486, Sept. 2023, doi: 10.3390/nano13172486.

[9] S. K. Sanjeeva et al., “Distilled technical cashew nut shell liquid (DT-CNSL) as an effective biofuel and additive to stabilize triglyceride biofuels in diesel,” Renewable Energy, vol. 71, pp. 81–88, Nov. 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2014.05.024.

[10] S. Gwoda, J. Valette, S. S. dit Sidibé, B. Piriou, J. Blin, and I. W. K. Ouédraogo, “Use of cashew nut shell liquid as biofuel blended in diesel: Optimisation of blends using additive acetone–butanol–ethanol (ABE (361)),” Cleaner Chemical Engineering, vol. 9, p. 100117, June 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.clce.2024.100117.

[11] D. Ike, M. Ibezim-Ezeani, and O. Akaranta, “Cashew nutshell liquid and its derivatives in oil field applications: an update,” Green Chemistry Letters and Reviews, vol. 14, pp. 618–631, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.1080/17518253.2021.1991485.

[12] “Marine fuels blended with Cashew Nutshell Liquid biofuel.” Accessed: Dec. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.skuld.com/topics/environment/air-pollution/marpol-annex-vi/marine-fuels-blended-with-cashew-nutshell-liquid-biofuel/

[13] J. Bullermann, N.-C. Meyer, A. Krafft, and F. Wirz, “Comparison of fuel properties of alternative drop-in fuels with standard marine diesel and the effects of their blends,” Fuel, vol. 357, p. 129937, Feb. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2023.129937.

[14] B. S. Kadjo, M. K. Sako, K. A. Diango, C. Perilhon, F. Hauquier, and A. Danlos, “Production of a high-energy solid biofuel from biochar produced from cashew nut shells,” Cleaner Engineering and Technology, vol. 21, p. 100776, Aug. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.clet.2024.100776.

[15] D. Sangaré, K. W. Yee Chung, J. Blin, C. Lanvin, J. Valette, and L. V. De Steene, “Thermal degradation and reactivity of cashew nut shell liquid constituents,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 507, p. 160866, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2025.160866.

[16] “Cashew nut biofuel blends present major operational challenges for vessels,” Brookes Bell. Accessed: Dec. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.brookesbell.com/news-and-knowledge/article/cashew-nut-biofuel-blends-present-major-operational-challenges-for-vessels-159292/

[17] A. Bates and T. Marsden, “Cashew nutshell liquid as a biofuel: use of additives to improve engine operability,” Zurich, Switzerland, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://papers2025.cimaccongress.com/pdf/CIMAC_paper_167.pdf